Growing old means that people you once viewed as old are now younger than you. Life is always safest when you are buffered on all sides. We buffer ourselves with family and friends. Money is a buffer. The battlefield is safest if you’re the person in the middle, not the edges. Life’s edges bring great things and they bring ruin. Those two people at the Antarctic-level extremes, those who live with the howling winds and who are nearest the gossamer border between life and death are the just-born infant and the elderly contemplating death. They are closer to each other than one might consider.

So it is good to always have people ahead of you on that slowly-advancing conveyor belt to the grave. Barring inconvenient events like accidental death, you’ve got it made. You can watch the clock and calculate everything down to the minute.

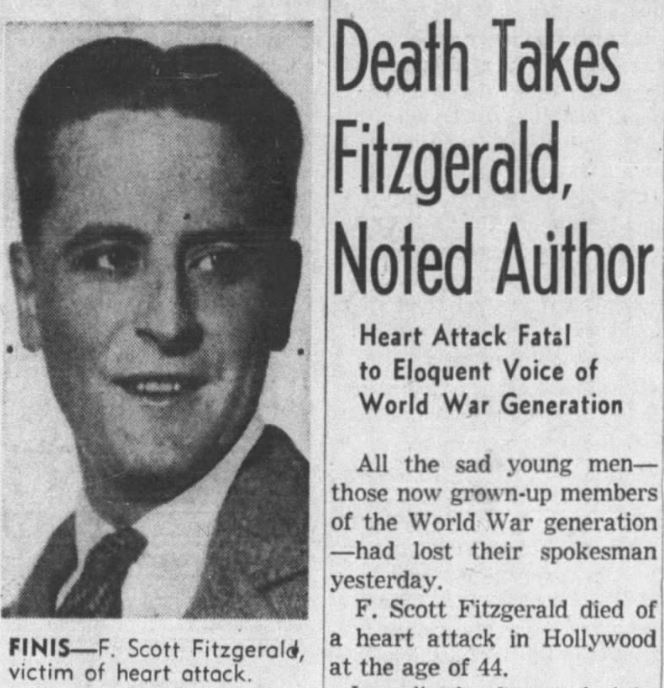

For most of my life, I viewed F. Scott Fitzgerald’s death as being right on the money, not premature at all. By then, his powers as a fiction writer had passed and he was living in Hollywood, pounding out screenplays and treatments, and living with gossip columnist Sheilah Graham, who was eight years Fitzgerald’s junior. It was an awkward matchup: an alcoholic novelist of former greatness and a gossip columnist of present popularity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald died on December 21, 1940. He was 44 years old, ten years younger than me. How is this possible? It’s possible because you realize that the definition of old when you are young is continually shifting. Yet eventually this shift comes to a halt, and you’re the one at the very edge.

Only six inches down and to the left, we learn that Ruth Slenczynska is laid up in bed:

With a surname like Slenczynska and a profession like pianist, one night think that she is Pole whose American tour was interrupted by appendicitis. But no, Miss Slenczynska comes from the decidedly American city of Sacramento, California, which lies at the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers. At age 93, Miss Slenczynska is still very much with us, reportedly living in Manhattan and giving piano lessons.

Cast your mind back once more, because Ruth Slenczynska is known as the last living link to legendary composer Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Slenczynska remembers that:

[Rachmaninoff] took me to the window, he said, “Look down at those trees, mimosa trees. And I want you to make a sound that has the golden color of mimosa in it.” I said, “How do you put color into a sound?” I never imagined the concept of color in a sound. I said, “Show me.” Now, that was the big advantage of being nine years old because a child just naturally asks.