It was a plane crash that killed 32 people, mainly illegal immigrants, and spawned Woody Guthrie’s song “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos).” For over 70 years, “Deportee” has come to signify the heartlessness of the American public, media, and law enforcement system towards illegal immigrants.

Recorded by Joan Baez, Kingston Trio, Hoyt Axton, Nanci Griffith, Concrete Blonde, Billy Bragg, Bruce Springsteen, and countless others, “Deportee” is a tight little package that protests what Guthrie considered to be racist mistreatment of the passengers before and after the accident. One typical contemporary mainstream media approach to the song comes from NPR, seeking to connect the 1948 deportation of 32 Mexican nationals with Trump administration immigration policies, saying that the immigrants’ “death [was] marked by anonymity when their names were lost in the accident.”

Except it wasn’t quite that way. The truth is a little more nuanced and less cruel than Guthrie made it out to be.

The Crash in Los Gatos

On January 28, 1948, a DC-3 plane carrying 32 people went down in rugged Los Gatos Canyon, near Coalinga, California, about 200 miles south of the San Francisco Bay Area. The crash killed the 32 people on board: 28 Mexican nationals, all men except for one woman, and four Americans. The Americans were a husband-and-wife pilot/stewardess team, Frank and Billie Atkinson; co-pilot Marion Ewing; and Immigration Inspector Frank Chaffin.

A road crew working in the area saw the plane go down and they were the first responders. Some bodies were strewn so far away from the plane that newspaper accounts at the time speculated that some of the men had tried to jump before the plane crashed. No solid explanation for the crash was ever produced.

Living in New York at the time, Woody Guthrie likely picked up the New York Times on January 29 and, seeing only the names of the four Americans listed and none of the Mexican nationals’ names, wrote about how the unnamed Mexicans were left “To fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil / And be called by no name except deportees.”

Since no names are supplied in the newspaper account, Guthrie makes up a few names:

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye, Rosalita,

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria;

You won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane,

All they will call you will be “deportees”

Attempts Made to Identify Bodies

Some have speculated that Guthrie’s song was only uninformed and well-meaning. Since Guthrie did not read past that first initial account, he did not know that officials “eagerly sought” the names of the Mexican nationals on the second day. Yet because the crash was not a local story, the New York papers did not extend their coverage beyond that first day.

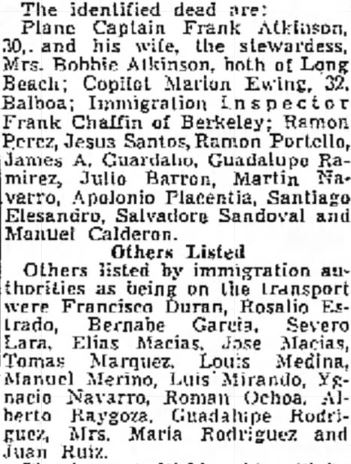

On the day of the crash, even the local Fresno and Bakersfield, California newspapers did report just the names of the four Americans and none of the Mexican nationals. But already by the second day, as reported by the Bakersfield Californian, both American and Mexican officials were working to identify the names of the Mexicans. Another local newspaper, the Fresno Bee, listed every Mexican national confirmed or believed to be on that doomed flight.

By sifting through the burning debris and mangled bodies, officials were able to positively identify 11 of the Mexicans; that is, they matched a body to an identity. Another 16 names that were listed as being on the transport list but not matching bodies were still publicly listed by immigration officials and published in the newspapers.

One aspect that complicated matters, according to I.F. Nixon, regional immigration director in San Francisco, was the fact that all were “agricultural workers who had slipped across the border without a passport or had overstayed their work permits.” So, in any kind of fiery plane crash, identification is difficult. Identifying the Mexicans in the Los Gatos crash was made even more difficult due to the pervasive lack of identification. Some were workers overstaying their work permits as part of the Bracero Program of the 1940s that standardized living conditions and a living wage for migratory workers. Thus, some of the workers were braceros who had timed out their permit and were now forced to leave.

In the end, positive identification of the remaining bodies was simply not possible due to the incredible impact of the plane crash and subsequent fire. Fresno County Deputy Coroner L.R. Webb said, “The rest may never be identified, so badly were the bodies broken and burned.”

Facts

Though Guthrie’s version of the story is overwrought and incomplete, some facts do remain:

- All 28 Mexicans were buried unidentified in a mass grave at Holy Cross Cemetery, Fresno, California.

- After that first identification, no attempts were made by officials to contact families of the Mexicans.

- The location of immigration guard Frank Chaffin’s remains are unknown, but he is marked on the mass grave memorial with the Mexican nationals.

- Marion Harlow Ewing (b. 1915) the co-pilot, was buried at Ivy Lawn Memorial Park, Ventura, California.

- Both Francis Atkinson and Lillian (Billie) Atkinson are buried at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, Rochester, New York.

- Subsequent writers such as Tim Z. Hernandez in his book All They Will Call You give a more complete version of the story. Hernandez spent six years searching for families of the dead and he was instrumental in obtaining funding for a new memorial that lists the names of all of the dead.

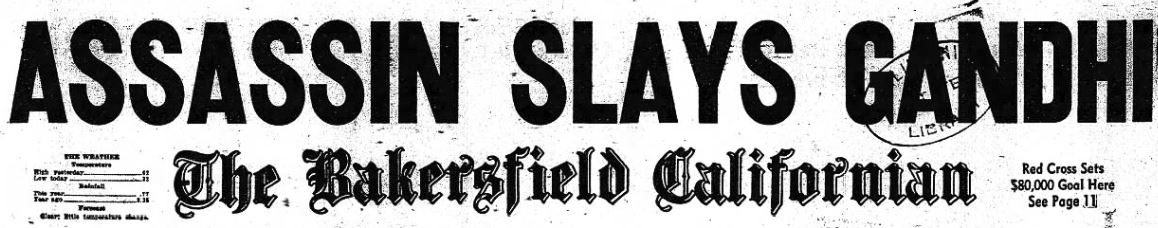

- By the third day, media reports of the Los Gatos crash and practically all other new items were buried by an event of international importance: Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated.