Zeppelins, despite their mammoth size, are by nature secretive modes of transport. Even when they plied the skies on a regular basis, zeppelins were largely misunderstood by the general public. I think I will puke if I read another book with an overly simplistic wrap-up like this:

And the the fiery destruction of the Hindenburg effectively marked the end of the airship age. The End.

God bless my Time-Life Books Epic of Flight series book, The Giant Airships, but that’s pretty much the neat ‘n’ tidy way they wrap up this whole, complicated saga. Nothing is that neat. There were many factors that contributed to the demise of airship travel (or I should say lull, since it is starting to come back) in the late 1930s. One tiny factor, out of perhaps hundreds, is the fact that helium, the heavier but safer gas, came mainly from two sources: the U.S. and Russia. In other words, not in Germany. But I digress.

That said, let’s look at one super-cool, secret part of the airships: the sub-cloud or spy basket.

Sub-Cloud Facts

As one crewman described the experience of being in a sub-cloud:

There I hung, exactly as if I had been in a bucket, down a well.

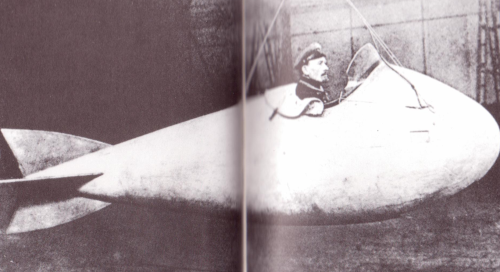

A sub-cloud was an aerodynamic “car” that was lowered on a cable below the zeppelin for purposes of spying or simply “spying” the conditions below the clouds.

- Often, the sub-cloud hung up to 500 feet below the zeppelin. Sometimes, the sub-cloud would be lowered as far as 750 or even 1000 meters–well over half a mile.

- Because of the isolation and lack of comfort, the sub-cloud could be equipped with a wicker chair, chart table, electric lamp, compass, and telephone.

- The support wire was steel with a brass core, and would also be used as the telephone line.

- Later spy baskets were not so much “baskets” as they were fully aerodynamic, fish-shaped cards–with fins, tails, and even small windshields.

- Crewmen loved one aspect of the sub-cloud: because smoking was forbidden on the hydrogen-filled airship, the sub-cloud was one place where they could smoke.

Lehmann and the Observation Car

Graf Zeppelin officer and Hindenburg Captain Ernst A. Lehmann, in his classic book The Zeppelins, describes the first usage of what he calls the “observation car”:

I did not see the preparations, but they must have been bungled somewhere. When the airship had reached a sufficient height Strasser got into the little car and gave the signal which would lower it a half mile below the ship. About 300 feet down, while the winch was allowing the cable to unwind slowly but steadily, the tail of the car became entangled with the wireless aerial. It caught the car and tilted it upside down. The cable meanwhile continued unwinding from the winch above and was beginning to dangle in a slack loop below Strasser, who only saved himself from being tipped out by clinging to the sides of the car with a deathlike grip. Suddenly the aerial gave way, sending the car and Strasser plunging down until it brought up at the end of its own cable with a sickening jolt. It was not a propitious introduction for the new device.